Technology

How to Measure a Portfolio’s Performance

Rarely anymore does investing get seen as a privilege of the rich. That gets proven by a recent Gallup survey that shows that over one hundred and fifty million Americans now invest in stocks. While this percentage is still below the ones noted before the housing market crash of 2008, it is still the highest in thirteen years. Hence, US residents are again waking up to the fact that building wealth is a long-term process available to most individuals with regular income. And to successfully trade securities, one must show long-haul focus and discipline. For that to happen, people need to build varied investment portfolios, implementing sound trading strategies that have track records of yielding double-digit annual returns.

Per research from Personal Capital, the average age when people start investing in the US is 33, with Saxo claiming that Gen Z members prefer financial stocks, followed by real estate and technology assets. Naturally, investment styles differ, but a core foundational principle for most is diversification. Like any sphere, the investing one also has its language, and the primary questions everyone must ask when building their portfolio is how much they want to spend monthly, how much help they require when investing, what are their goals, their risk profile, and what assets can best lead them to hit projected milestones.

It is too essential to recognize that chosen asset allocation can get out of whack sometimes, and a degree of rebalancing may be on the docket to restore an investment portfolio to its original makeup. To properly assess when this is mandatory, investors must know to track the performance of their securities and then make adjustments when necessary, selecting which underweighted ones to purchase with the proceeds from off-loading their overweight assets. Ascertaining one’s financial situation and aims is the first step in constructing a portfolio. Then follows the monitoring of one’s investments. To help with that process, here are five methods of measuring a portfolio’s performance.

Sharpe Ratio

William Forsyth Sharpe is a University of California Ph.D. who taught Finance at Stanford University. A 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize winner in the area of Economic Sciences. He gets touted as one of the financial masterminds of the 20th century, renowned for creating the Sharpe ratio for risk-adjusted investment analysis. It is a reward-to-variability index developed in the mid-1960s, measuring the performance of an investment (a portfolio or security) stacked up to a risk-free asset after adjusting the risk factor. For the past three decades, it has become one of the most preferred risk/return measures in finance, with a sizable deal of its establishment getting credited to its simplicity.

Many financial experts would describe this ratio in rudimentary terms by stating that it compares the return on investment with its risk. Mathematically, the formula can get rudimentary explained in its simplest form as the return of the portfolio minus the risk-free rate divided by the standard deviation of the portfolio’s excess return. The latter gets derived from the variability of returns for a set of intervals summing up to the considered total performance sample. Essentially, the Sharpe ratio compares a portfolio’s projected or historical returns relative to a benchmark with the expected or historical variability of such returns. It mainly gets used to evaluate a portfolio’s risk-adjusted performance.

A vital issue many have with investment managers using it is that it can get manipulated by elongating the return measurement intervals. That produces a lower estimate of volatility, boosting an apparent risk-adjusted returns history.

Sortino Ratio

In truth, the Sortino ratio is nothing more than a variation or a modification of the Sharpe formula. Instead of using the total standard deviation of portfolio returns, it utilizes the asset’s standard deviation of negative portfolio returns (downside deviation) to differentiate harmful volatility from the overall one. It ignores the above-average returns in exchange for solely focusing on the downside deviation, believing it to be a far better proxy for the risk of a portfolio fund. Many think by doing this, a better view of a portfolio’s risk-adjusted performance gets provided.

It is named after Frank A. Sortino, the Director of the Pension Research Institute and former San Francisco State University finance professor. What Sortino’s ratio does is it looks at an asset or portfolio’s return and then minimizes the risk-free rate. Then, it splits that sum by the downside deviation of the asset. So, if the expected returns are 20%, the risk-free rate is 10%, and the downside deviation is 4%. The ratio would be 2.5. Without question, this is a handy method for portfolio managers, investors, and analysts to assess an investment’s return for a given degree of bad risk. Many mutual funds implement this statistical tool, noting that they do so because it tends to supply fairly accurate reads.

Treynor Measure

Most financial managers have nicknamed the Treynor ratio the reward-to-volatility one. Again, people will say that this is an iteration of the Sharpe, and they are not wrong because it is a ranking criterion only. It does not quantify the value added to active portfolio management. The goal of this metric for performance is to show how much extra returns got generated for each unit of risk incurred by a group of investments. The danger/risk referred to here is the systematic one measured by a portfolio’s beta. For the non-investment-savvy readers, a Beta is a measure of a portfolio’s systematic risk compared to an entire market, often the S&P 500. As a rule of thumb, stocks that boast betas of more than 1.0 get viewed as more volatile than the S&P 500. Beta also gets implemented in CAPM, or the capital asset pricing model that describes the link between the expected return for assets and systematic risk. CAPM is considered by most as an instrument for pricing risky securities.

The formula for the Treynor Ratio is subtracting the risk-free rate from the portfolio return and then dividing this by the beta of the portfolio. The goal here is to try to gauge how successful an investment will be in terms of yielding compensation to investors for taking on the noted risk.

The focal downside of the formula is its backward-looking outlook, as investments will probably behave differently than how they did so before. The success of applying this principle heavily relies on implementing quality benchmarks to measure beta.

Its inventor is American economist Jack Lawrence Treynor, a mentor of Fischer Black, one of the creators of the Black–Scholes model, and a protégé of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics winner, Franco Modigliani.

Benchmark Returns with Indexes

Being able to continuously measure the performance of multiple investments at any given time delivers a substantial advantage in the process of trading securities. Thankfully, that can be done nowadays using various software that can create different kinds of charts and tables using automatically updated data in seconds.

The terms indexes and benchmarks are often utilized interchangeably by both laypeople and casual investors. Yet, they are unique ones that delineate different things. An index is a statistical tool designed to gauge market performance over time. For example, the DJIA, or Dow Jones Industrial Average, is a securities index created to assert the accomplishment of stocks representing a significant chunk of the US economy. While a benchmark, by definition, serves as a standard, a reference point by which other things get judged.

With a portfolio management app, users can set up benchmark columns to track a stock’s performance vs. its index. Note, by default, most investing software will use the S&P 500 index as a comparison benchmark, but that can get modified in a setting’s window.

Also, today, investors have multiple benchmarks to choose from in apps. Some of these are fixed-income and traditional equality benchmarks. Plus, users have more exotic ones on hand, invented for real estate, hedge funds, derivatives, and other types of investments. But explaining these is outside the scope of this article.

In general, most investors look at broad historical indexes as benchmarks when evaluating how their trades are doing. Those investors that own stocks frequently, if not religiously, check out the Nasdaq 100, the mentioned DJIA, and the S&P 500 to see – where the market is at. That is simple, even without an app, because these indexes get tracked by worldwide financial media outlets. Active management investors must ensure that they are implementing proper benchmarks that their returns get compared to at distinct intervals. And sadly, research shows that most actively traded portfolios fail to beat benchmarked indices after factoring in taxes and fees. Thus, that is the reason so many people claim that it is wiser to take the passive indexed route to invest practices.

Jensen Measure

Michael Cole Jensen is an Alma mater at the Macalester College University of Chicago and has worked in economics for sixty years, teaching at Harvard University and the University of Rochester during his illustrated career in American economics. In academic circles, he gets credited for playing an essential role in corporate governance, stock option policies, and capital asset pricing models. Though, by far, his most massive contribution to finance gets considered the so-called Jensen’s alpha/measure.

What is Jensen’s alpha? It is another risk-adjusted performance measure, an ex-post alpha that gets utilized to figure out the abnormal return of a portfolio/security over the theoretical expected return. The theoretical return most commonly gets predicted by the capital asset pricing model, but other market models can be used that incorporate statistical methods to predict the appropriate risk-adjusted return of an asset. As discussed above, the capital asset pricing model, or CAPM for short, uses beta as a multiplier. So, Jensen’s measure quantifies the excess returns accrued by a portfolio above the returns projected by the capital asset pricing model.

The formula for Jensen’s alpha is taking the portfolio return and taking away from it the total of the sum of the risk-free rate when one adds to it the beta multiplied by the total of the expected market return with the risk-free rate subtracted from it. That may be a bit complicated for some to grasp in text form and require further exploration. But, the value of the alpha can be positive – showing outperformance, negative – displaying underperformance, and zero – neutral performance.

Critics of Jensen’s measure generally state that the disadvantage of this approach is that it does not take into account the portfolio’s volatility, only its expected return. And it misses out on attributes like skewness and kurtosis, pointing to Eugene Fama’s efficient market hypothesis (EMH) as something fans of Jensen’s measure should look into and analyze.

Parting Thought

These and other tools can deliver pivotal information to investors regarding how effectively their money is working for them. Remember, portfolio performance measures should have a determining part in future investment decisions, but they only show part of the story. Just because stocks are not doing well at the moment or for the past several months, that does not mean they have little long-term value. So, there is something to be said about having long-haul perspectives and beliefs in specific companies, ones that may be on the verge of innovating or those whose accurate value will only get recognized down the line. Still, without adequately assessing risk-adjusted returns, no one can view the entire investment big picture. Not having such sight can indirectly lead to misadvised decisions that can have dramatic consequences. Therefore, it is smart to measure performance periodically.

How to Measure a Portfolio’s Performance

Rarely anymore does investing get seen as a privilege of the rich. That gets proven by a recent Gallup survey that shows that over one hundred and fifty million Americans now invest in stocks. While this percentage is still below the ones noted before the housing market crash of 2008, it is still the highest in thirteen years. Hence, US residents are again waking up to the fact that building wealth is a long-term process available to most individuals with regular income. And to successfully trade securities, one must show long-haul focus and discipline. For that to happen, people need to build varied investment portfolios, implementing sound trading strategies that have track records of yielding double-digit annual returns.

Per research from Personal Capital, the average age when people start investing in the US is 33, with Saxo claiming that Gen Z members prefer financial stocks, followed by real estate and technology assets. Naturally, investment styles differ, but a core foundational principle for most is diversification. Like any sphere, the investing one also has its language, and the primary questions everyone must ask when building their portfolio is how much they want to spend monthly, how much help they require when investing, what are their goals, their risk profile, and what assets can best lead them to hit projected milestones.

It is too essential to recognize that chosen asset allocation can get out of whack sometimes, and a degree of rebalancing may be on the docket to restore an investment portfolio to its original makeup. To properly assess when this is mandatory, investors must know to track the performance of their securities and then make adjustments when necessary, selecting which underweighted ones to purchase with the proceeds from off-loading their overweight assets. Ascertaining one’s financial situation and aims is the first step in constructing a portfolio. Then follows the monitoring of one’s investments. To help with that process, here are five methods of measuring a portfolio’s performance.

Sharpe Ratio

William Forsyth Sharpe is a University of California Ph.D. who taught Finance at Stanford University. A 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize winner in the area of Economic Sciences. He gets touted as one of the financial masterminds of the 20th century, renowned for creating the Sharpe ratio for risk-adjusted investment analysis. It is a reward-to-variability index developed in the mid-1960s, measuring the performance of an investment (a portfolio or security) stacked up to a risk-free asset after adjusting the risk factor. For the past three decades, it has become one of the most preferred risk/return measures in finance, with a sizable deal of its establishment getting credited to its simplicity.

Many financial experts would describe this ratio in rudimentary terms by stating that it compares the return on investment with its risk. Mathematically, the formula can get rudimentary explained in its simplest form as the return of the portfolio minus the risk-free rate divided by the standard deviation of the portfolio’s excess return. The latter gets derived from the variability of returns for a set of intervals summing up to the considered total performance sample. Essentially, the Sharpe ratio compares a portfolio’s projected or historical returns relative to a benchmark with the expected or historical variability of such returns. It mainly gets used to evaluate a portfolio’s risk-adjusted performance.

A vital issue many have with investment managers using it is that it can get manipulated by elongating the return measurement intervals. That produces a lower estimate of volatility, boosting an apparent risk-adjusted returns history.

Sortino Ratio

In truth, the Sortino ratio is nothing more than a variation or a modification of the Sharpe formula. Instead of using the total standard deviation of portfolio returns, it utilizes the asset’s standard deviation of negative portfolio returns (downside deviation) to differentiate harmful volatility from the overall one. It ignores the above-average returns in exchange for solely focusing on the downside deviation, believing it to be a far better proxy for the risk of a portfolio fund. Many think by doing this, a better view of a portfolio’s risk-adjusted performance gets provided.

It is named after Frank A. Sortino, the Director of the Pension Research Institute and former San Francisco State University finance professor. What Sortino’s ratio does is it looks at an asset or portfolio’s return and then minimizes the risk-free rate. Then, it splits that sum by the downside deviation of the asset. So, if the expected returns are 20%, the risk-free rate is 10%, and the downside deviation is 4%. The ratio would be 2.5. Without question, this is a handy method for portfolio managers, investors, and analysts to assess an investment’s return for a given degree of bad risk. Many mutual funds implement this statistical tool, noting that they do so because it tends to supply fairly accurate reads.

Treynor Measure

Most financial managers have nicknamed the Treynor ratio the reward-to-volatility one. Again, people will say that this is an iteration of the Sharpe, and they are not wrong because it is a ranking criterion only. It does not quantify the value added to active portfolio management. The goal of this metric for performance is to show how much extra returns got generated for each unit of risk incurred by a group of investments. The danger/risk referred to here is the systematic one measured by a portfolio’s beta. For the non-investment-savvy readers, a Beta is a measure of a portfolio’s systematic risk compared to an entire market, often the S&P 500. As a rule of thumb, stocks that boast betas of more than 1.0 get viewed as more volatile than the S&P 500. Beta also gets implemented in CAPM, or the capital asset pricing model that describes the link between the expected return for assets and systematic risk. CAPM is considered by most as an instrument for pricing risky securities.

The formula for the Treynor Ratio is subtracting the risk-free rate from the portfolio return and then dividing this by the beta of the portfolio. The goal here is to try to gauge how successful an investment will be in terms of yielding compensation to investors for taking on the noted risk.

The focal downside of the formula is its backward-looking outlook, as investments will probably behave differently than how they did so before. The success of applying this principle heavily relies on implementing quality benchmarks to measure beta.

Its inventor is American economist Jack Lawrence Treynor, a mentor of Fischer Black, one of the creators of the Black–Scholes model, and a protégé of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics winner, Franco Modigliani.

Benchmark Returns with Indexes

Being able to continuously measure the performance of multiple investments at any given time delivers a substantial advantage in the process of trading securities. Thankfully, that can be done nowadays using various software that can create different kinds of charts and tables using automatically updated data in seconds.

The terms indexes and benchmarks are often utilized interchangeably by both laypeople and casual investors. Yet, they are unique ones that delineate different things. An index is a statistical tool designed to gauge market performance over time. For example, the DJIA, or Dow Jones Industrial Average, is a securities index created to assert the accomplishment of stocks representing a significant chunk of the US economy. While a benchmark, by definition, serves as a standard, a reference point by which other things get judged.

With a portfolio management app, users can set up benchmark columns to track a stock’s performance vs. its index. Note, by default, most investing software will use the S&P 500 index as a comparison benchmark, but that can get modified in a setting’s window.

Also, today, investors have multiple benchmarks to choose from in apps. Some of these are fixed-income and traditional equality benchmarks. Plus, users have more exotic ones on hand, invented for real estate, hedge funds, derivatives, and other types of investments. But explaining these is outside the scope of this article.

In general, most investors look at broad historical indexes as benchmarks when evaluating how their trades are doing. Those investors that own stocks frequently, if not religiously, check out the Nasdaq 100, the mentioned DJIA, and the S&P 500 to see – where the market is at. That is simple, even without an app, because these indexes get tracked by worldwide financial media outlets. Active management investors must ensure that they are implementing proper benchmarks that their returns get compared to at distinct intervals. And sadly, research shows that most actively traded portfolios fail to beat benchmarked indices after factoring in taxes and fees. Thus, that is the reason so many people claim that it is wiser to take the passive indexed route to invest practices.

Jensen Measure

Michael Cole Jensen is an Alma mater at the Macalester College University of Chicago and has worked in economics for sixty years, teaching at Harvard University and the University of Rochester during his illustrated career in American economics. In academic circles, he gets credited for playing an essential role in corporate governance, stock option policies, and capital asset pricing models. Though, by far, his most massive contribution to finance gets considered the so-called Jensen’s alpha/measure.

What is Jensen’s alpha? It is another risk-adjusted performance measure, an ex-post alpha that gets utilized to figure out the abnormal return of a portfolio/security over the theoretical expected return. The theoretical return most commonly gets predicted by the capital asset pricing model, but other market models can be used that incorporate statistical methods to predict the appropriate risk-adjusted return of an asset. As discussed above, the capital asset pricing model, or CAPM for short, uses beta as a multiplier. So, Jensen’s measure quantifies the excess returns accrued by a portfolio above the returns projected by the capital asset pricing model.

The formula for Jensen’s alpha is taking the portfolio return and taking away from it the total of the sum of the risk-free rate when one adds to it the beta multiplied by the total of the expected market return with the risk-free rate subtracted from it. That may be a bit complicated for some to grasp in text form and require further exploration. But, the value of the alpha can be positive – showing outperformance, negative – displaying underperformance, and zero – neutral performance.

Critics of Jensen’s measure generally state that the disadvantage of this approach is that it does not take into account the portfolio’s volatility, only its expected return. And it misses out on attributes like skewness and kurtosis, pointing to Eugene Fama’s efficient market hypothesis (EMH) as something fans of Jensen’s measure should look into and analyze.

Parting Thought

These and other tools can deliver pivotal information to investors regarding how effectively their money is working for them. Remember, portfolio performance measures should have a determining part in future investment decisions, but they only show part of the story. Just because stocks are not doing well at the moment or for the past several months, that does not mean they have little long-term value. So, there is something to be said about having long-haul perspectives and beliefs in specific companies, ones that may be on the verge of innovating or those whose accurate value will only get recognized down the line. Still, without adequately assessing risk-adjusted returns, no one can view the entire investment big picture. Not having such sight can indirectly lead to misadvised decisions that can have dramatic consequences. Therefore, it is smart to measure performance periodically.

Artifical Intelligence

How AI Can Help You Redeem Points for Maximum Value

In this digital age, everything is changing rapidly due to emerging technologies. Nowadays, artificial intelligence (AI) is improving customer experiences, and focuses more on personalization by evaluating the behavior, and preferences of the customers. It is also greatly beneficial for the accumulation of reward points, as it can suggest effective ways to maximize your reward point values, according to your previous redemption options. Generative AI is now able to guide you on, how to spend your credit card reward points. It also provides advice on, how to book flights in exchange for rewards points.

Use Of AI For Maximum Reward Points

Artificial Intelligence (AI) utilizes tasks based on human intelligence, recognizing patterns and predicting them based on these recommendations. You can gain more benefits, by applying AI and ML to loyalty programs. It can improve customer segmentation, and personalization by evaluating user behavior, and preferences. This helps you in providing more personalized offers, and rewards that you can earn easily.

These technologies also enable you to identify various methods to earn more points. These methods include the automation of some tasks, from which you automatically gain reward points such as paying monthly bills automatically, applying for sign-up bonuses, and reaching the threshold of quarterly spending.

How To Redeem Points for Maximum Value Using AI

With the help of generative AI, everyone can get maximum points using reward credit cards, to redeem for traveling or other services. AI is now suggesting custom travel packages, based on the user’s preferences like travel destinations, specific dates, likings, etc. These suggestions are also beneficial in improving the user experience, with the development of reward programs. Here are some methods to redeem maximum reward points with the help of AI:

- Social Media Incorporation

Social media consists of a large amount of user data, and everyone loves to upload their activities and preferences on it. AI can evaluate this data, by asking for user permission, and identify the user’s likings and his everyday life. With this data, AI can suggest relative exchanging options, that suit you best, based on your activities. For example, if you post about outdoor activities on social media, AI will suggest redemption options related to them, like traveling, dining, hiking, etc. These also improve the user experience, by providing more engaging and relative redemption options.

- Effective Guidance Of Spending Reward Points

Generative AI is extremely helpful in guiding you, on how to spend your reward points for maximum value. You only need to write a prompt, and add some other preferences that you want in it, and it will generate a response related to it with complete guidance. It also suggests some places, where you can redeem your reward points effectively. You can also obtain information about a specific service, by knowing how much they value your reward points, and what their services are being offered in exchange for reward points. All this data generated from AI is based on reality, as it has upgraded algorithms, that are beneficial in achieving real-time data.

- Suggest Specific Credit Cards

AI can also help you, to use specific credit cards for redemption options, by suggesting which one suits best for maximum value. It is highly beneficial for those, who hold multiple credit cards and do not know, which card they can use for redemption, to achieve maximized value. You can also get help from AI, in this matter by asking about your credit cards, which gives more value for specific services.

Certain credit cards are specifically for limited services, where you can redeem your points. Some offer redemption options on services, like dining and other hoteling services, traveling, groceries, etc. Some companies provide services based on the type of credit card you hold, as enterprise credit cards have more value for their reward points.

- Evaluate The Value of Credit Card Points

In the past, every credit card point held the value of 1 penny each, but nowadays these values vary over time from 0.2 cents to 2.8 cents. Some card issuers tell their users about the value of their points, when they are useless, or have a minimum value. You need to have complete knowledge about, how much value your points hold currently. AI assistants can guide you, by providing extensive information, and telling you the average value of the reward points considered throughout the world these days. These assistants are integrated with various algorithms, and are capable of gaining information from various financial websites, to discover an overall average value. It helps you in not redeeming your reward points, when they hold an extremely low value.

- Effective Planning Of Redemption Options

There are so many AI services available on the internet, that guide you according to your prompts. These services provide you with complete information on the service, which you want to receive in exchange for your reward points. These assistants provide good recommendations about numerous company services, based on their charges and values, offered for reward points redemption. You can save most of your reward points, by receiving effective information about every service provider. You can plan for your vacations or business trips from this information, based on the offered values on your reward points. Your reward points value will be determined, according to the service provider you choose, as some services cost more reward points and some are less expensive. Some AI assistants also helps credit card users save and make money online with their cards.

Final Thoughts

You can extract the most beneficial information from various AI models. These are extremely helpful for you, to redeem your reward points for maximum value. These models suggest numerous exchange options according to your interests, and preferences. AI also prevents you from wasting your reward points for extremely low cost.

There are numerous card-monitoring applications, integrated with AI models, that offer some automatic tasks like signing up for bonuses, reminding you about the points, that are near expiration, paying monthly bills automatically, and applying for quarterly bonuses. There will be more advancements in the future, that will enhance the reward points further. Many companies are partnering with credit card issuers, and offering its services as a redemption option which results in maximizing the value of your reward points.

Technology

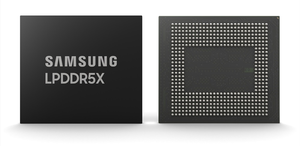

Samsung develops the fastest DRAM chip for AI applications in the industry

In a groundbreaking development, Samsung has announced the creation of the industry’s first low-power double data rate 5X (LPDDR5X) DRAM chip for AI applications. The new chip boasts high performance of up to 10.7 Gbps, marking a significant improvement in both speed and capacity compared to previous models.

Low-power, high-performance LPDDR chips are becoming increasingly important in the on-device AI market. Samsung’s latest LPDDR5X products, developed with 12 nanometer-class process technology, are the smallest in size among existing LPDDR chips, further cementing the company’s position as a leader in the low-power DRAM sector.

A company spokesperson stated, “Samsung will continue to innovate and deliver optimized products for the upcoming on-device AI era through close collaboration with customers.” Mass production of the LPDDR5X is set to commence in the second half of the year, pending verification by mobile application processor and device providers.

The unveiling of Samsung’s LPDDR5X DRAM chip represents a significant step forward in the field of AI technology. The chip’s impressive performance and capacity enhancements are expected to further drive the adoption of on-device AI solutions in various industries. This groundbreaking innovation is sure to set a new standard for memory solutions tailored for AI applications.

Technology

PM Modi expresses strong interest in Zoho’s rural development model: Sridhar Vembu

New Delhi, April 17 (IANS) – Zoho Founder and CEO, Sridhar Vembu, revealed that Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed interest in Zoho’s rural development model in Tenkasi district, Tamil Nadu during his recent meeting. PM Modi praised the company’s efforts in creating high-tech capabilities and jobs in rural areas.

During an election rally in Ambasamudram, PM Modi met Vembu to discuss Zoho’s rural development through R&D model. Vembu expressed gratitude towards PM Modi for taking the time to understand and appreciate the company’s operations in Tenkasi as a model of rural development.

“PM Modi came to Ambasamudram which is close to my village. Even in the middle of his hectic campaign schedule, he gave me time to meet him and brief him on our rural development through R&D model and on creating high-tech capability and jobs in rural areas,” Vembu shared on social media.

Vembu highlighted that PM Modi showed keen interest in Zoho’s Tenkasi operations. He praised the Prime Minister’s leadership and expressed his support for his continued health and service to the nation. Zoho, founded in 1996 and headquartered in Chennai, employs over 15,000 individuals globally.

During his rally in Ambasamudram, PM Modi criticized the DMK in Tamil Nadu, alleging that they conspired with the Congress to hand over the Katchatheevu island to a foreign nation. PM Modi emphasized his commitment to developing a ‘Viksit Tamil Nadu’ along with a ‘Viksit Bharat’ for overall progress.

The interaction between PM Modi and Zoho’s CEO highlights the government’s interest in innovative rural development models like the one implemented by Zoho in Tenkasi district. The meeting signifies a recognition of the potential for high-tech job creation in rural areas leading to localized economic growth and development.

Photos1 week ago

Photos1 week ago65+ Georgina Rodriguez Hot, Sexy, Naked Pics: Top Bikini Photos of Cristiano Ronaldo’s Girlfriend

Photos1 week ago

Photos1 week ago65+ Top Anveshi Jain Hot and Sexy Pictures: Bikini Photos of ‘Gandii Baat’ Actress

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days ago8 Sapna Sharma Hot Web Series for 2024 (18+ Only)

Web Series6 days ago

Web Series6 days ago15 Hot Sharanya Jit Kaur web series to binge-watch online

Photos1 week ago

Photos1 week ago95+ Monalisa Hot, Sexy, and Bikini Photos of Bhojpuri Actress ‘Antara Biswas’

Web Series4 days ago

Web Series4 days ago6 Ankita Singh Web Series, Age, Net Worth, Husband, and Instagram Posts

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoPriya Mishra Web Series Names List (18+ Age Only)

Entertainment18 hours ago

Entertainment18 hours ago8 Best Sapna Sappu Web Series to Watch This Weekend